Interpretability in Deep Learning

Mis à jour :

Deep learning has been all the rage for the last few years. Powered by ever-increasing power, memory and bigger datasets, neural networks are easier to train than before. However, despite the tremendous success of certain applications (computer vision, Go and Dota…), the theoretical understanding of what a neural net actually takes more time to burgeon.

Gap between practice and theory

Paradoxically, despite being supported by significant theoretical results (next section), there is no guarantees that deep learning will find a good solution in practice.

Going deep or not?

The first attempts to measure the expessive power of neural network in the 1960s trace back to two papers

- [On the structure of continuous functions of several variables, David A. Sprecher, 1965]

- Another one by Kolmogorov

that are largely inspired from the Kolmogorov–Arnold representation theorem (or superposition theorem):

Any multivariable continuous function $f$ can be written as a finite compositions of continuous functions $\Phi$ and $\phi$ of a single variable and the binary operation of addition $+$. Mathematically:

In 1989, Frederico Girosi and Tomaso Poggio review Kolmogorov‘s theorem and show that it is irrelevant in the context of networks for learning because of the following reasons:

- The proof based on hashing is discontinuous.

- There is no room for learnability and generalizability

- One would need an infinite amount of samples to learn a periodic function on $\mathbb{R}$

The same year, George Cybenko demonstrates that any continuous function defined on a compact set $[0, 1]^{d}$ (for a finite $d$) can be approximated by a neural net with one hidden layer and a sigmoid activation. This astounding result, known today as the Universal approximation theorems is one of the first success in this direction. Two years later, Kurt Hornik showed that that the result hold for any non-constant activation function; therefore suggesting that this property lies within the Multi-Layer Perceptron itself. Along other discoveries, this theorem made a dent in the AI winter.

Most recently, a lot of work has been done to further understand the impact of the depth and the width of these networks. Especially, reseachers try to answer the question: Why deep and cheap learning work so well? Some suggests these results can be explained by physics.

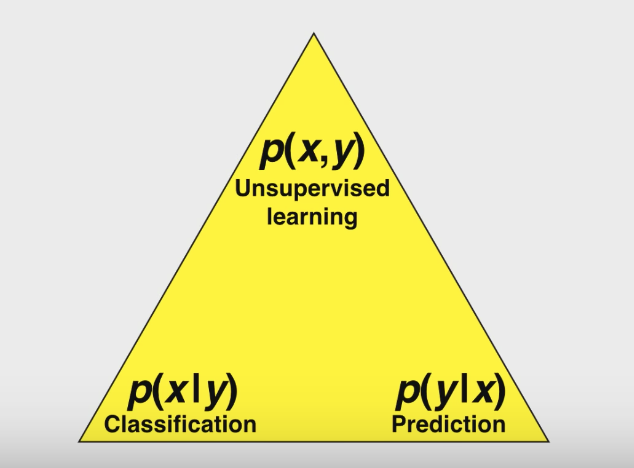

At its core, deep learning is about function approximation (with most function being probability distributions):

Mathematically, neural networks are a very particular class of functions: alternate linear and non-linear operations.

The big question is then how long and large should it get? i.e. how many ressources (neurons, parameters) does the neural network require to approximage a given function?

Consider a black and white image with one million pixels. Then, there are $2^{10^{6}}$ possible images of this size, which is more than the number of atoms in the universe.

With this in mind, it’s schoking that deep learning works given its much (much) lower amount of parameters.

The reason is best explained from a physics perspective. But let’s first write Bayes formula:

and take the logs:

where $H$ is the Hamiltonian, an operator which correspond to the total energy of the system. Here $\mu is the bias$. Written as is, we obtain:

Using the softmax layer $\sigma$, we end up with a formula for the desired classification probability vector $p(x)$:

This recasting is useful because the Hamiltonian tends to have properties making it simple to evaluate. But the point of all this is that if we can compute the Hamiltonian vector $H(x)$ with some $n$-layer neural net, we can evaluate the desired classification probability vector $p(x)$ by simply adding a softmax layer. The $\mu$-vector simply becomes the bias term in this final layer.

It manages to pull of such incredible feats by combinatorial swindle.

PHYSICS

Sotfmax = Hamiltonian (log proba) is simple (polynomial for the universe)

Reduce the number of parameters with physics principle:

- Locality: Information tend to be confined and linked in a neighborhood. ?

- Symmetry:

Real world images comes from Hamiltonian generated shit?

Four neurons in one hidden layer, we can accomplish multiplication.

Cheap learning: do well with small number of parameters.

In Physics, most process (see data) are generated one step at a time. It is the reason why going deep is better because it undo the complications nature made one step at a time.

Once the deep neural net is generated, is it possible to flatten it into a more shallow one?

- No flattening theorem

What is a special class of function can DL handle?

What is a special class of function can Physics handle?

We show how the success of deep learning could depend not only on mathematics but also on physics: although well-known mathematical theorems guarantee that neural networks can approximate arbitrary functions well, the class of functions of practical interest can frequently be approximated through “cheap learning” with exponentially fewer parameters than generic ones. We explore how properties frequently encountered in physics such as symmetry, locality, compositionality, and polynomial log-probability translate into exceptionally simple neural networks. We further argue that when the statistical process generating the data is of a certain hierarchical form prevalent in physics and machine-learning, a deep neural network can be more efficient than a shallow one. We formalize these claims using information theory and discuss the relation to the renormalization group. We prove various “no-flattening theorems” showing when efficient linear deep networks cannot be accurately approximated by shallow ones without efficiency loss; for example, we show that n variables cannot be multiplied using fewer than 2n neurons in a single hidden layer.

Depth simplifies the approximation/estimation task:

- Why deep: examples of depth vs. layer size compromises with explicit bounds

- [Why does deep and cheap learning work so well? Henry W. Lin, Max Tegmark, David Rolnick, 2016] : multiplication of n input variables : binary tree ~ log n multiplication nodes, while flat requires sum_{all 2^n configurations} (approximating a multiplication node by 4 neurons, of any smooth [developable] activation function)

- [Representation Benefits of Deep Feedforward Networks, Matus Telgarsky, 2015] : example: function = 2^m consecutive small triangles /\/\/\/\/\/\ = ( /\ ) $o^m$ (composed m times with itself) ==> representable with a thin deep network. In a flat network: 2 layers require provably 2^{m/2} nodes, sqrt(m) layers requier 2^sqrt(m) nodes, etc.

- Mhaskar, Poggio, Liao, 2016 : architecture suitability for function estimation: Theorem: if function to estimare = computational tree of input variables, then required number of samples to learn a similar-shaped network: d instead of exp d

- deep is sufficient: [ResNet with one-neuron hidden layers is a Universal Approximator, Hongzhou Lin, Stefanie Jegelka, NIPS 2018]

Does it work? When?

Examples of successes and failures of deep learning vs. classical techniques (random forests) –> successes in computer vision: due to handling image properties well: explicit geometry handling, invariance to translation, hierarchical models (see Chapter 2) –> random forest (e.g.), without geometry information (difficult to incorporate), would require massively more data to learn anything (no generalization power [from a variable to the next one] without geometry knowledge) –> on the opposite: if no data structure : random forest can do the job; if small data: neural network won’t be able to –> success in RL: –> as a function of processing power: running Alpha-Go/0 on a huge GPU farm for hours, having played zillions of games: is it a success? –> 44 million training games (more than Humanity total), 4 hours on 5000 TPU = more than 2 years of single TPU = thousands of years on a single CPU? –> sounds like very slow learning; wouldn’t other methods perform as well with such computational power? [slide 25, Benjamin Recht]

Gap between classical Machine Learning and Deep Learning

Forgotten Machine Learning basics (Minimum Description Length principle, regularizers, objective function different from evaluation criterion) and incidental palliatives (drop-out)

- Reminder: ML setup: samples (x_i, y_i), estimate f: x_i –> ~ y_i, loss function quantifying goodness of output, search for inf_{f in predefined parameterized family} sum_i Loss(f(x_i), y_i) + regularizer(f)

Minimum Description Length: origin of the ML setup (theoretical justification, from information theory) . find the shortest program that given (x_i) outputs (y_i) : Occam’s razor (shorter explanation = the best one, will generalize better to new examples) : Solomonoff’s prior: proba(f) = 2^{- Kolmogorov complexity(f) } . usual approximation of Kolmogorov complexity : number n of parameters (AIC) or n log N (BIC: N = number of samples) . in the Bayesian probabilistic setup, choose a prior of functions, e.g. prior(f) = exp(- ||f||) for some norm, measure the likelihood of f to produce the right answer: p(y | f(x)), then MDL rewrites as the ML setup: p(f) = product_i p(y_i|f(x_i)) x prior(f) –> E(f) = -log p(f) = sum_i …

- some ML / optimization basics seem to be not really true anymore (no overfit with millions of parameters?) . millions of parameters : what about MDL? . possible to train networks with millions of parameters without overfitting (still generalize well, i.e. small gap between train and test error) . and this with fewer examples than parameters : estimator convergence? . highly non-convex optimization in a high-dimensional space : thought to be very hard and to be avoided . add noise in the optimization process, it helps . train to optimize a criterion, but evaluate on another one… (because the evaluation criterion is not differentiable or doesn’t have good gradient properties) . when trying to solve a new task: check first the model is able to overfit (!) (in contrast to picking a regularized search space)

[joke: deep_learning_vs_classical_ML.png]

A closer look at overfitting [Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization, Chiyuan Zhang, Samy Bengio, Moritz Hardt, Benjamin Recht, Oriol Vinyals, ICLR 2017] & http://dalimeeting.org/dali2019/workshop-optimization.html#TrainingontheTestSetandOtherHeresies –> huge models can do the job (might not overfit) [slides 9 & 11, Benjamin Recht] –> they can completely overfit too (learn random labels) : shown theoretically & experimentally –> theory: network size required for overfitting is very small (given the sample, to fit random labels): Theorem: There exists a two-layer neural network with ReLU activations and 2n + d weights that can represent any function on a sample of size n in d dimensions. ==> capacity is not the issue (Rademacher or Vapnik-Chervonenkis), rather control / regularization / telling which functions are preferable –> how to know when overfitting or not? / how to prevent overfitting? [to be discussed later] –> possible regularizers: weight decay, dropout, data augmentation –> not clear, from experiments (not sufficient/necessary even though do help) –> early stopping = regularizer –> SGD, as a optimization process, regularizes also

Palliatives for regularization

–> drop-out : at each time step, select randomly half of neurons and temporarily drop them (replace with 0) –> robustness to noise in neuron activity a_i <> requiring df/da_i ~ 0 ==> not far from an explicit regularizer ||nabla_x f|| –> ensemble point of view: average over probabilistic architectures

–> what about adding functional regularizers? [Amal Rannen Triki, Maxim Berman, Matthew Blaschko, unpublished, http://dalimeeting.org/dali2019/workshop-optimization.html#Functionnormsandregularizationindeepnetworks] –> NP-hard to compute the functional norm, because NP-hard to estimate whether a neural net is the function 0… –> but stochastic approxim = ok

–> early stopping (i.e. picking the trained model M(training time) that has lowest validation error) Bishop (1995a) and Sjoberg and Ljung (1995) argued that early stopping has the effect of restricting the optimization procedure to a relatively small volume of parameter space in the neighborhood of the initial parameter value theta_0. –> no time to get specialized too much (too far from generic initialization) into overfitting minima –> same for weight decay then –> optimization =/= usual gradient descent till convergence, but rather just an optimization process (pile of recipes, selected manually by trial and error, to have a positive effect on neural network training)

–> the optimization noise acts as a regularizer [Poggio, varied publications, http://cbcl.mit.edu/people/poggio/poggio-new.htm]

- hessian def>0 ==> SGD noise good ; but if degenerated:

- SGD overfits after a while in certain cases (if Hessian not def>0), because train pulls back =/= test

rendre def>0 la Hessian: ajouter regulariseur sur les poids ( w _2) - contrary to: weight norm (de la matrice de connexion) + RELU ==> regularies mais pas def>0

–> overparameterization helps (hot topic)

to understand this, need some more detailed optimization landscape analysis

Optimization landscape / properties [small break]

–> + permut-inv(neurones) ==> lots of minima… (in factorial(N)) (or Poggio’s proof with Bezout’s theorem for polynomial-activation networks) –> so many parameters ==> local minima = very good (because huge neighborhood) (different to classical optim) –> but also: even more: saddle points –> Dauphin et al. (2014) : random Hessians are much more likely to be saddle points than definite positive.

Lots of works on convergence:

- random initialization + SGD on an overparameterized network : converges (well) not very far from init (2-layer network) [Learning Overparameterized Neural Networks via Stochastic Gradient Descent on Structured Data, Yuanzhi Li, Yingyu Liang, NIPS 2018]

- good convergence (under assumptions): [Gradient Descent Finds Global Minima of Deep Neural Networks, Simon S. Du, Jason D. Lee, Haochuan Li, Liwei Wang, Xiyu Zhai, arXiv]

[Stanford class on CNN for Visual Recognition, http://cs231n.github.io/neural-networks-1/#arch] : good summary about neural net complexity and performance : `` Based on our discussion above, it seems that smaller neural networks can be preferred if the data is not complex enough to prevent overfitting. However, this is incorrect - there are many other preferred ways to prevent overfitting in Neural Networks that we will discuss later (such as L2 regularization, dropout, input noise). In practice, it is always better to use these methods to control overfitting instead of the number of neurons. The subtle reason behind this is that smaller networks are harder to train with local methods such as Gradient Descent: It’s clear that their loss functions have relatively few local minima, but it turns out that many of these minima are easier to converge to, and that they are bad (i.e. with high loss). Conversely, bigger neural networks contain significantly more local minima, but these minima turn out to be much better in terms of their actual loss. Since Neural Networks are non-convex, it is hard to study these properties mathematically, but some attempts to understand these objective functions have been made, e.g. in a recent paper The Loss Surfaces of Multilayer Networks https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.0233 . In practice, what you find is that if you train a small network the final loss can display a good amount of variance - in some cases you get lucky and converge to a good place but in some cases you get trapped in one of the bad minima. On the other hand, if you train a large network you’ll start to find many different solutions, but the variance in the final achieved loss will be much smaller. In other words, all solutions are about equally as good, and rely less on the luck of random initialization. ‘’ ==> don’t evaluate the complexity of the network (or its optimization) by its number of neurons (not a good proxy) : larger networks are easier to train (more local minima, but good ones, to the opposite of small architectures) –> then, how?

ML fundamentals (MDL) are still there!

MDL principle is lost? number of parameters = huge, but:

- no precision needed

- high redundancy –> network compression: impressive rate (pruning, quantization, tensor factorization…: > 100 ) –> run online video object detection on a smartphone [Bayesian Compression for Deep Learning, Christos Louizos, Karen Ullrich, Max Welling, NIPS 2017]

actually, BIC = just an approx of MDL, not valid here –> [The Description Length of Deep Learning Models, Leonard Blier, Yann Ollivier] : compression, not of network, but of (network, labels | inputs). –> summary: back to the original MDL, deriving another, simple expression to estimate neural network complexity, which does not rely on parameter number –> NB: we consider networks with probabilistic output, i.e. one does not compute a single value y_i given an input x_i, but a distribution p_predicted(y_i), denoted p_predicted(y_i | x_i) –> start with always the same neural network initialization (chosen so that it is short to describe, e.g. the random seed) –> at each training time step t : get new samples (x_i), predict for each of them an associated distribution probability p_t(y_i|x_i), and compute how much it costs to describe the true y_i according to that predicted distribution (better prediction means smaller cost): -log p_t(true label y_i | x_i) –> total description length of this training algorithm: neglectible constant + sum_t sum_{i in batch at time t} - log p_t(y_i | x_i) where p_t is computed by the network at training step t (when not knowing the y_i of its new batch yet). –> note that this quantity is related to the performance of the network, its trainability, but not directly the number of its parameters –> MDL is still compatible with deep learning! –> train many models and pick the one with the lowest description length: it will generalize better, according to the MDL principle / Solomonoff prior –> can spot the part due to parameters (weights) [information stored in the network] <> uncertainty in output : . compute the description length if one had known the trained network from the beginning: sum_{all samples i from all batches} -log p_trained(y_i|x_i) . compute the difference with the real total description length above : the difference expresses how much information is stored in the weights of the trained network

Architectures as priors on function space, initializations as random nonlinear projections

–> change of design paradigm –> classical ML : design features by hand vs deep learning : meta-design of features : design architectures that are likely to produce features similar to the ones you would have designed by hand –> an architecture = a parameterized family (by the neural network’s weights) –> still a similar optimization problem (find the best parameterized function), just, in a much wider space (many more parameters)

–> architecture = prior on the function –> prior : –> as a constraint (what is expressible or not with this architecture) ? but already huge capacity –> most often not useful ==> probabilistic prior (what is easy to reach or not) –> good architecture : with random weights, already good features (or not far) [random = according to some law, see later] –> in classical ML, lots of works on random features + SVM on top (usually from a kernel point of view); random projections –> most of the performance is due to the architecture, not the training (in some cases at least) : fitting just a linear classifier on top of the random network doesn’t decrease much the accuracy: [On Random Weights and Unsupervised Feature Learning, Andrew M. Saxe, Pang Wei Koh, Zhenghao Chen, Maneesh Bhand, Bipin Suresh, and Andrew Y. Ng, ICML 2011] (old: LeNet architecture, but confirmed with VGG by another paper) –> visualization of the quality of random weights in known architectures by reconstrucing the input, from the k-th layer activations [VGG with random weights]: no big information loss: [A Powerful Generative Model Using Random Weights for the Deep Image Representation, Kun He, Yan Wang, John Hopcroft, NIPS 2016] ==> training whole or keeping random “non-linear projections”: just about optimization order or speed (train last layer first) –> bias of the architecture (i.e. proba on possible functions to learn): example: Fourier spectrum bias [On the spectral bias of neural networks, Rahaman & al, NIPS 2018] : lower frequencies (i.e. big objects) are learned first

–> random initialization: random but according to a chosen law that induce good functional properties

- avoid exploding or vanishing gradient (ex: activities globally multiplied by a constant factor > 1 or < 1 at each layer) –> Xavier Glorot initialization, or similar : [Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks, Xavier Glorot, Yoshua Bengio, AISTATS 2010] . multiplicative weights: uniform over [-1 / sqrt(d), +1 / sqrt(d)], or Gaussian(0, sigma^2 = 1/d) where d = number of inputs of the neuron (justification: if weights w_i are Gaussian and inputs x_i of variance 1, sum_i w_i x_i will still be of variance ~ 1) . multiply by an activation-function-dependent factor if needed (eg: ReLU divide variance by 2, since they are 0 over half of the input domain, so, correct by * 2) . biases: 0

- [Which neural net architectures give rise to exploding and vanishing gradients? NIPS 2018, Boris Hanin] . check the Jacobian df/dx at initialization . turns out that, with n_l = “number of neurons in layer l”: . variance(df/dx) is fixed = 1/n_0 . var( df/dx ^2), i.e. the fourth moment E[ df/dx ^4 ] is lower- and upper- bounded by terms in exp(sum_{layers l} 1/n_l ) ==> sum 1/n_l is an important quantity ==> avoid many thin layers; if on a neuron budget, choose equal size for all layers

–> designing architectures easy to train . training “deep” networks : not really deep in terms of distance between any weight to tune and the loss information (except for orthonormal matrices…) for easier information communcation (through the backpropagation) –> ResNet architectures (see next chapter) –> or add intermediate losses (idem) . we saw that overparameterized networks (i.e. large layers) seem to be easier to train . is depth required? Not an easy question. [Do Deep Nets Really Need to be Deep? https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6184] : learning a shallow network doesn’t work; learning a deep one works; training a shallow one to learn the deep one works, and possibly with no more parameter than the deep one ==> “good architecture” is about “more likely to get the right function”; better, future optimizers might make smaller architectures more attractive

Refs:

Laisser un commentaire